Today’s world is only a reflection of the past that has shaped it. Through the centuries, countless migrations, diffusions, and movements of people have contributed to the rich and diverse ethnic tapestry of our world. No place has a greater ethnic and genetic diversity than Tanzania, with more than 120 different groups of Bantu, Nilotic, and Cushitic origins, among others.[1] Within East Africa, we can see the genetic impact of the Bantu Migrations and their formative input on the region’s ethnic history. Using AncestryDNA and other services, people have just begun to unlock this history and learn more about how these Sub-Saharan migrations shaped their own genetic story.

Origins and Pathways of the Bantu Migration

- 1. Bantu Origins

- 2. The First Wave of Expansion with the split into Eastern and Western Branches

- 3. The Urewe Nucleus

- 4. – 7. Expansion Southward

- 8. Eastward movement by the Western Branch

- 9. The Congo Nucleus

- 10. The Last Wave of Bantu Migration

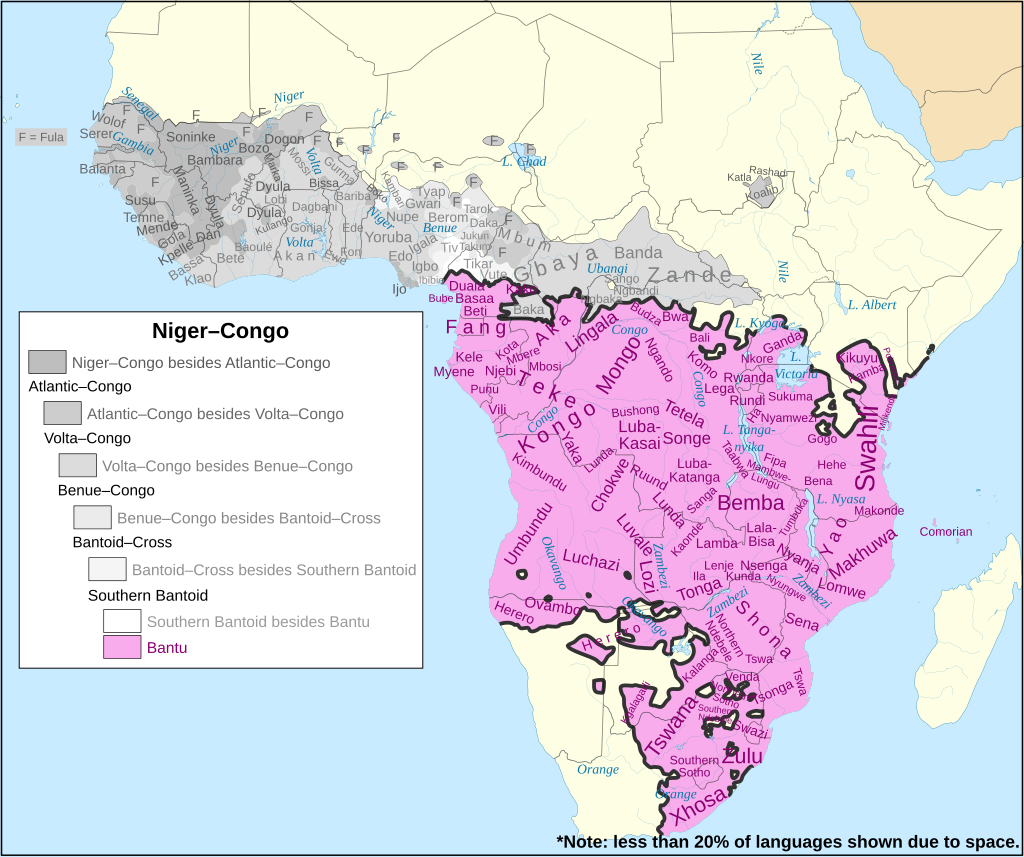

Starting around the present border of Cameroon and Nigeria, the first waves of the Bantu migration reached the upper Congo Basin and the headwaters of the Nile.[2] This marked the first expansion of the Niger-Congo speaking groups beyond West Africa. Other linguistically related groups such as the Igbo, Akan, and Wolof remained on the Atlantic coast and did not join the Bantus on their journey.[3] The original inhabitants of the land soon to become home to the Bantu migrants, were of Khoisan, Central African Forager, Cushitic, and sometimes Nilo-Saharan origin.[4]

The Western Branch of the migration travelled down the Atlantic coast and Congo River system southward, reaching as far as Angola before 500 BC.[5] Another set of Bantu-speaking groups traversed the Central African Rainforest and began to expand into the savannas to the south. Over the subsequent centuries, a separate branch of the expansion diverged and reached the African Great Lakes region, eventually populating the Indian Ocean’s coastline.[6] After this, these Eastern Bantu groups began to migrate southward pushing the Central African Forager communities deeper into the rainforest and the Khoisan peoples further south. While some of these previously established groups moved into more remote locations, others were assimilated into Bantu-speaking communities. The Bantus’ largely superior technologies, with their iron weapons and tools, as well as their more advanced agricultural practices, supported a larger population growth and fueled expansion.

While many assumed that the Bantu migrations marked a population replacement, there is evidence that there was also considerable admixture and even language shift, complicating the ethno-genetic picture.[7] This is further complicated by the presence of later waves of Bantu migration. According to Nurse and Philippson, people from the Urewe Nucleus of Eastern Bantu groups helped populate East Africa, while the separate Congo Nucleus made up of people from the Western Branch also moved into the regions of East and South Africa.[8] These overlapping migrations of separated, distinct populations create a diverse Bantu background, that is further admixed with the pre-expansion inhabitants of the area and groups involved in the Indian Ocean trade.

Cushitic groups, for example, had moved down into the Lake Turkana region from the Ethiopian Highlands as early as 5,000 years ago, with some of the earliest evidence of livestock herding in the region being credited to these groups. Centuries later, Northern Cushites from the Horn of Africa expanded into the area that is now known as Kenya and helped to populate some areas around the coast. Nilotic groups had also previously settled around Lake Turkana and journeyed southward into Tanzania after the Bantu Expansion.[9] Later, trade on the coast introduced Indian Ocean peoples into the gene pool, with Arabs and Indians mingling with coastal Cushitic and Bantu peoples.[10]

How Does AncestryDNA Breakdown Bantu Ancestry?

Genetic services like Ancestry.com are starting to show the hereditary implications of these centuries of migrations and population mixing for the average consumer. While there are some issues with low levels of testing among Sub-Saharan Africans, and the fact that AncestryDNA does not reveal the ethnic background of their reference samples, there is still valuable information to be gained by examining Ancestry’s data. The test results of East Africans, while not generalizable, are indicative of the aforementioned migrations.

With AncestryDNA testing, there are three different Bantu categories, “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples,” “Eastern Bantu Peoples,” and “Southern Bantu Peoples.” In the AncestryDNA reference panel, these groups have 533, 167, and 183 reference samples, respectively. Additionally, in internal accuracy tests, “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” and “Southern Bantu Peoples” were found to be highly accurate, while “Eastern Bantu Peoples” had an accuracy of around 85%.[11] The “Southern Bantu Peoples” category is roughly representative of ancestry from Bantu groups in Mozambique, South Africa, and Botswana. Following the proposed path of Bantu Expansion, these areas would have been partially populated by groups moving down from the Urewe Nucleus near the African Great Lakes, making genetic overlap with the “Eastern Bantu Peoples” category plausible. Many of the samples that will be discussed in the next paragraph registered some DNA in the “Southern Bantu Peoples” category; however, I do not believe this represents the true flow of Bantu genes but is instead attributable to the close genetic similarity between groups in East and South Africa, given their shared origin. The other two categories are likely roughly analogous to the Bantu nuclei that populated East Africa, with Urewe descendancy likely linked to “Eastern Bantu Peoples” and the Congo Nucleus to the “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” category, at least within the context of East Africa.

AncestryDNA’s Samples

Fonte Felipe, an AncestryDNA researcher, compiled data on AncestryDNA testers from Sub-Saharan Africa. Using Felipe’s data, we can see some of the effects of the Bantu Migrations. A Tanzanian of Western Ha origin, a Bantu-speaking group from the northwestern area of Lake Tanganyika, scored highest in the category “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” with a secondary category of “Eastern Bantu Peoples.” Given the proximity of Lake Tanganyika to the Congo region, it makes sense that this category would be higher for a person from this area. Among other groups in East Africa this pattern is not repeated, however. Among two samples from the Jita and Kuria groups near Lake Victoria, “Eastern Bantu Peoples” scored significantly higher with 83-68% of their DNA being attributed to this category. “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” was in a distant second place with 30-11% of the Jita and Kuria DNA being placed in this group. The Urewe culture was centered around Lake Victoria and radiated outward into neighboring Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi,[12] possibly explaining the high “Eastern Bantu Peoples” content of the North Tanzanian Bantu-speaking groups.

Samples from Tutsis in Burundi and Rwanda also support this hypothesis, with “Eastern Bantu Peoples” being their highest scoring category, while “Ethiopia & Eritrea” and “Somalia” make up the better part of their remaining ancestry, likely representative of Cushitic heritage. “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” is comparatively a much lesser component of Tutsi lineage, with it accounting for 16% of one sample and 4% of the other. Additionally, trace amounts of Khoisan and Central African Forager heritage were observed in these samples. In Uganda, a sample from the north of the nation scored 100% “Eastern Bantu Peoples” while another of undetermined region was evenly split between this category and “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples.” Amongst eight samples from the Kikuyu, Taita, and Kisii peoples of southern Kenya, “Eastern Bantu Peoples” remains the largest category by percentage with it hovering around 50% for all participants. Within this sample group, “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” only reaches above 20% twice, showing a variation consistent with the Jita and Kuria samples from northern Tanzania. There were also trace amounts of “Ethiopia and Eritrea,” “Somalia,” and “Khoisan, Aka & Mbuti Peoples,” which points to Cushitic, Khoisan, and Central African Forager admixture in southern Kenya, most similar to the trace profile of Tutsis in Rwanda and Burundi.

A Kenyan of “Swahili” origin showed the large divergence between the genes of people on the East African coast and those of the interior. The Swahili results scored highest in the “Ethiopia and Eritrea” category, this, in conjunction with the “Somalia” category’s appearance in the results is indicative of Cushitic origin. Next highest is “Eastern Bantu Peoples” with only a modest contribution from “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples.” The sample also shows trace regions of “Northern India” and “Iran/Persia,” reflecting the diverse source populations of the traders on the Swahili Coast.[13]

Genetic Influences of the Bantu Expansion in AncestryDNA Data

Overall, while samples from southern and western Tanzania were lacking, it is safe to say that there is some support for the timeline and location of Bantu migrations set forth by Nurse and Philippson. In areas closest to the Urewe Nucleus, “Eastern Bantu Peoples” predominates, and areas nearer to the Congo Nucleus have much higher “Cameroon, Congo & Western Bantu Peoples” admixture. Furthermore, Cushitic influence was present in the northern parts of East Africa presenting evidence of their migrations southward from the Ethiopian Highlands and Horn of Africa. Khoisan and Central African Forager ancestry were also observed in trace amounts throughout the African Great Lakes region, showing that some intermarriage and assimilation into Bantu-speaking groups likely occurred, rather than outright population replacement at the time of the Bantu Expansion.

Unfortunately, AncestryDNA did not have a good category for estimating Nilotic ancestry as of their 2020 update, much to the chagrin of researchers and genealogists alike. Demonstrating this, a sample from a Ugandan of Aringa and Kakwa heritage, Nilo-Saharan groups, had a mixture of “Khoisan, Aka & Mbuti Peoples,” “Eastern Bantu Peoples,” “Senegal,” and “Mali” as their results. The unlikely presence of Senegalese and Malian peoples in precolonial Uganda shows that Nilo-Saharan DNA was most likely just being presented with the “next best” category. Senegal and Mali both have a robust history of admixture with Sahelian groups such as the Fula,[14] potentially making these categories the closest proxies for Nilo-Saharan DNA. The same can likely be said for the presence of “Khoisan, Aka & Mbuti Peoples” above trace levels, this may just be the result of not having Nilotic reference samples. This limited the accuracy of AncestryDNA tests for those of Eastern African heritage but should not present a problem when examining the difference between Bantu source populations for the region, given how different Nilotic groups are genetically distinct from the rest of the Sub-Sahara.[15]

Tanzanian Ethnic Diversity In-Person

My experiences and travels in Tanzania helped to showcase the diversity of East African peoples. The nation is a microcosm of the region itself, with Bantu, Cushitic, and Nilotic ethnic groups within north Tanzania alone. In Moshi, the largest segment of the population is made up of Chagga people, an eastern Bantu group. As we headed west from Moshi toward Arusha and finally the national parks, the Maasai began to become more predominant. With a main center around Ngorongoro and the Serengeti, the Maasai have been the dominant ethnic group in this area since the 17th and 18th centuries.[16] On the way to the parks in Karatu, I also met some people of Iraqw origin, a Cushitic group that had inhabited the area since before the Maasai migration into the region. They make up the majority of the district population in Karatu.[17] Without the valuable context of meeting these people, and learning about their origins, any analysis of Tanzanian or regional genetics would be incomplete. Experiencing these differences for myself fundamentally changed my perspective on East African culture in a way that could not have occurred otherwise. All the different traditions and cultures were unique, and in some ways similar to my own.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Bantu Migration

East Africa has a wide assortment of ethnic groups, that together produced the unique and varied cultural differences that make the region so rich and diverse. From the many origins and ancestries of the Cushitic, Nilotic, Khoisan, and Central African Forager groups that comingled with the migrant Bantu communities, to the Arab, Indian, and Persian traders that dotted the Swahili Coast, the peoples that populated East Africa formed a distinct regional identity. As these populations coalesced, they shaped the genetic narrative of the Sub-Sahara, forming the unique nation we know as Tanzania.

Editor’s Note: The data used in this article corresponds with AncestryDNA’s 2020 Update, which was the most recent data available at the time of writing. While the conclusions are based on available data and historical migration models, this analysis is informal and exploratory rather than a formal statistical study. It is meant to provide insight into the patterns of Bantu migration and admixture using the current genetic resources available to the average consumer. For the most up-to-date data, readers should consult AncestryDNA’s latest white paper, as their categories have evolved since this analysis was conducted.

[1] Nag, O. S. (2020, October 23). The Culture of Tanzania. WorldAtlas. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-culture-of-tanzania.html

[2] McEvedy, C. (2008). The Penguin Atlas of African history. Paw Prints.

[3] Niger-Congo Language Family. MustGo.com. (n.d.). Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://www.mustgo.com/worldlanguages/niger-congo-language-family/

[4] Ambrose, S. H. (1986). Hunter-gatherer adaptations to non-marginal environments: an ecological and archaeological assessment of the Dorobo model. Sprache Und Geschichte in Afrika. 7 (2)

[5] Ehret, C. (2001). Bantu Expansions: Re-Envisioning a Central Problem of Early African History. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 34(1), 5–41.

[6] Irish, J. (2016). Tracing the “Bantu Expansion” from its source: Dental nonmetric affinities among West African and neighboring populations.

[7] Patin, E., Laval, G., Barreiro, L. B., Salas, A., Semino, O., Santachiara-Benerecetti, S., Kidd, K. K., Kidd, J. R., Van der Veen, L., Hombert, J.-M., Gessain, A., Froment, A., Bahuchet, S., Heyer, E., & Quintana-Murci, L. (2009). Inferring the Demographic History of African Farmers and Pygmy Hunter–Gatherers Using a Multilocus Resequencing Data Set. PLoS Genetics, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000448

[8] Nurse, D., & Philippson Gérard. (2003). The Bantu Languages. Routledge.

[9] Kiarie, M. (n.d.). Early migrations into East Africa. Enzi. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from http://www.enzimuseum.org/after-the-stone-age/early-migrations-into-east-africa

[10] LaViolette, A. (2008). Swahili Cosmopolitanism in Africa and the Indian Ocean World, A.D. 600–1500. Archaeologies, 4(1), 24–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-008-9064-x

[11] Adrion, J., Berkowitz, N., Noto, K., Sedghifar, A., Starr, B., Turissini, D., Wang, Y., & Wolf, A. (2021). Ethnicity Estimate 2021 White Paper, 1–41.

[12] Denham, T., Iriarte José, Vrydaghs, L., Van Grunderbeek, M.-C., & Roche, E. (2016). Multidisciplinary Evidence of Mixed Farming During the Early Iron Age in Rwanda and Burundi. In Rethinking Agriculture: Archaeological and Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives. Routledge.

[13] Felipe, F. (2021, April 30). Ancestry’s new African breakdown: Merely cosmetic changes? Tracing African Roots. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://tracingafricanroots.wordpress.com/2020/09/19/ancestrys-new-african-breakdown-merely-cosmetic-changes/#more-35298

[14] Danver, S. L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures, and Contemporary Issues. Routledge.

[15] Dobon, B., Hassan, H. Y., Laayouni, H., Luisi, P., Ricaño-Ponce, I., Zhernakova, A., Wijmenga, C., Tahir, H., Comas, D., Netea, M. G., & Bertranpetit, J. (2015). The genetics of East African populations: A Nilo-Saharan component in the African Genetic Landscape. Scientific Reports, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09996

[16] Maasai History and Culture. Basecamp Foundation USA. (2019, September 28). Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://basecampfoundationusa.org/the-maasai/maasai-history-and-culture/#:~:text=According%20to%20their%20oral%20history,17th%20and%20late%2018th%20century.

[17] Matthiessen, P., & Porter, E. (1998). The Tree Where Man Was Born. Harvill.

Leave a Reply